[ NOTE: If you would like to watch/listen to a “blogcast” of this post, click HERE ]

Years before H.G. Wells introduced us to his time traveller and marauding Martians, another writer was predicting what science might bring us in the future, for good or for ill. Once read on both sides of the Atlantic, he’s now all but forgotten. His name was Robert Duncan Milne and he was seeing moving pictures before there was even a strip of celluloid.

From Reality to Fantasy

Milne was born in Cupar in Scotland to a well-to-do family, the son of a minister, and received a fine education. But having shown talent for the Classics, he dropped out of Oxford University, and in 1868 he took the bold step of heading to America, all the way to the burgeoning state of California and a life of adventure.

Milne was born in Cupar in Scotland to a well-to-do family, the son of a minister, and received a fine education. But having shown talent for the Classics, he dropped out of Oxford University, and in 1868 he took the bold step of heading to America, all the way to the burgeoning state of California and a life of adventure.

After some years as a cook, a labourer and an itinerant shepherd, truly living the life of the New West, he re-emerged as an inventor in 1874, patenting a number of ideas, one of which seemed set to make him rich. It didn’t.

The next we know of him, he had morphed into a journalist and writer, contributing accounts of his roaming experiences in a well-respected publication, The Argonaut, which would be his literary home for many years, based as it was in the city that became his adopted physical home: San Francisco. Connected up to the east coast by the Pacific Railroad in 1869, its population would double over the following 20 years. Then, as now, it was a place for innovation and new thinking. Milne’s mind was in tune with this.

Maintaining the same documentary style, Milne began to write stories which were wildly imaginative and rich with new science. Often framed as if they were occurrences he had witnessed or encountered through his circle of acquaintance, they would include tales of global interconnected communication systems, a drone strike on San Francisco, surveillance culture and an ability to see the past through moving pictures.

In 1881 he published The Paleoscopic Camera in which he encounters a photographer named Millbank, whilst visiting the beautiful church of San Xavier del Bac in Arizona, near the Mexican border. Millbank has made an extraordinary discovery: used the right way, his photographic system can capture images of the past, from the resonances of light energy in the walls. Putting his head under the camera’s black cloth the writer sees years of events shooting past in fast time-lapse: images that Millbank can photograph.

Millbank is described as “a rather tall and slightly stooping figure, in a loose blue serge jacket and a slouched hat surmounting a bronzed and heavily-bearded face.” Although based in San Francisco, he has been “travelling here and there in Mexico and Central America”. For anybody well-versed in pre-cinema developments loud bells will now be ringing about a real person who fits this description very well: Eadweard Muybridge.

Muybridge’s sequence images of animals and human beings in motion are iconic, but he already had a powerful reputation as a photographer who could capture what others couldn’t. Having been acquitted of the murder of his wife’s lover on the extraordinary grounds of justifiable homicide at the start of 1875, Muybridge disappeared into Central America for a long time, later exhibiting the images he captured. It was in the five years after his return to San Francisco that he took the first of his famous sequences, sponsored by Leland Stanford (who was closely associated with The Argonaut) and then created a way to project them with his “Zoopraxiscope”.

It seems highly likely that Milne had witnessed one of his illustrated lectures, possibly even spent time with Muybridge, and would have been well aware of his story. But even though Muybridge was just capturing short cycles of motion, Milne saw the possibilities of photography capturing history in living detail.

It seems highly likely that Milne had witnessed one of his illustrated lectures, possibly even spent time with Muybridge, and would have been well aware of his story. But even though Muybridge was just capturing short cycles of motion, Milne saw the possibilities of photography capturing history in living detail.

A Secret Uncovered

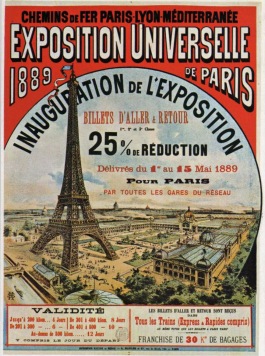

It was a subject that Milne would return to in more prescient detail eight years later when the story The Eidoloscope appeared in the same publication. Here the narrator encounters an inventor he knows: Mr. Espy, who has a lonely display table in the Paris Exposition. He claims to have a device that can play back visual scenes from the past the same way a phonograph can play back an audio recording. Although sceptical, the narrator finds himself bored over Christmas in a friend’s country house and so calls on Mr. Espy to give a demonstration – resulting in a terrible secret being revealed. In this case all the images are seen running in reverse as they move back in time, like a film on rewind.

I have done a decent audio recording of the story to save your eyes from the tiny print of the original, which can be found below. The first half is mainly full of the “science” of Espy’s device and the drama is more in the second half, so I won’t be deeply hurt if you skip forward to 19.18.

Milne could not have chosen a more apposite setting for encountering Mr. Espy. The Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889, in retrospect, reveals itself as an extraordinary confluence of those who first sought to capture motion with photography and those who would take it forward.

Edison had an impressive display there and headed over from New York in August to spend a month in the city. Back in Orange, New Jersey, his workers were still trying and failing to record micro-photographs on a cylinder (akin to the phonograph). But in Paris he spent time with Jules-Etienne Marey who had used paper film and early celluloid-like material to capture his “chronophotographic” sequences. On his return Edison ordered that they now start experimenting with rolls of film and so began work towards the Kinetoscope.

But that wasn’t all. Also featured at the exposition was the Electrical Tachyscope of Ottomar Anschütz with its short but incredibly vivid moving picture sequences, which Edison’s workers would also experiment with. Whilst in Paris Edison was a guest of honour at a dinner to celebrate 50 years of photography with other attendees that not only included Marey but also Antoine, Auguste and Louis Lumière – who would be his direct rivals six years hence.

But that wasn’t all. Also featured at the exposition was the Electrical Tachyscope of Ottomar Anschütz with its short but incredibly vivid moving picture sequences, which Edison’s workers would also experiment with. Whilst in Paris Edison was a guest of honour at a dinner to celebrate 50 years of photography with other attendees that not only included Marey but also Antoine, Auguste and Louis Lumière – who would be his direct rivals six years hence.

At the exposition at that very same time was another visitor, probably unknown to all of the above: William Friese-Greene. Quite aside from the brand new Eiffel Tower, scientific exhibits to see, the photographic congress and the pleasures of Paris, William had another reason to feel excited and happy. Having completed the prototype of a moving picture film camera a month or two previously, he had taken out a provisional patent along with his collaborator – a civil engineer, Mortimer Evans. As he took in the sights, back in London the scientific instrument makers Légé & Co were already working on the Mark II – a camera with a larger capacity and faster running speed, which would be ready in September.

From Fantasy to Reality

So Milne’s instincts were good. And even if his vision of a way of not only recording the present for the future but also capturing the past, has not yet been realised, there is one way that his story – which was reproduced in many publications – did leave an indelible mark on the future of film.

The first people to create a film camera and projector system with which they shot films and showed them to a paying public were not the Lumière brothers. Yes, you read me right: there was nothing about the premiere of the Lumière Cinématographe on the 28th December 1895 which constituted a significant first or the start of the film industry. That honour belongs to a group of people which included Woodville Latham and his two sons, plus the former Edison moving picture workers William Dickson and Eugene Lauste. They began their public film shows in New York in May 1895, which moved out to many American cities.

When the first results were shown to the press it was called a “Panopticon” (or “Pantoptikon”) but this was a confusingly overused word already applied to various forms of entertainment, including the magic lantern. Over the following weeks they searched around for an appropriately impressive name to launch it upon the world at large.

They found it, christening their projector “The Eidoloscope”. Milne must have been pleased.

If you’d like to know more about Robert Duncan Milne and his stories, start HERE.

For everything in the universe about Eadweard Muybridge, The Compleat Muybridge really is.

Thank you for this!

LikeLiked by 1 person