“When are you going to get to the point?” is an entirely justifiable cry to escape from you, my dear, (im)patient reader. Well, I have been working on something rather special, just for you. So I hope it will seem worth the wait.

To quickly recap the story so far and what we know:

- Between early 1889 and early 1891 William Friese-Green was involved in the creation of three distinct moving picture cameras.

- After the end of 1890 he was completely broke and had to stop inventing.

- Although he had to sell (almost) everything he owned in 1891, he kept hold of the cameras.

We know about the first camera because of the patent, plus photographs and drawings of it. We know about the second, stereoscopic one because of both the patent and because that camera is still in existence. For the third one, we don’t have a patent, a drawing, a photo or even a clear description, BUT over in the French film archives we have some of the film it took. And that could tell us quite a bit…

For instance, that it was around 60-65mm wide. That’s the large format still occasionally used by film-makers like Christopher Nolan and Quentin Tarantino. But remember that, at the time, celluloid wasn’t freely available in any widths smaller than that. The 35mm standard was still years away and was chosen partially because those Edison Kinetoscope images were only to be viewed in a peep-hole machine, so picture resolution didn’t have to be that high. With the poor resolution of film emulsions at that point in time, it was wise to use a larger format if you wanted to project the images.

For instance, that it was around 60-65mm wide. That’s the large format still occasionally used by film-makers like Christopher Nolan and Quentin Tarantino. But remember that, at the time, celluloid wasn’t freely available in any widths smaller than that. The 35mm standard was still years away and was chosen partially because those Edison Kinetoscope images were only to be viewed in a peep-hole machine, so picture resolution didn’t have to be that high. With the poor resolution of film emulsions at that point in time, it was wise to use a larger format if you wanted to project the images.

We also know that the film negative had been hand-perforated before being shot. There were nine round holes of 2mm diameter punched on both sides of each frame. It must have been a painstaking business to do in a darkroom – and pretty hit-and-miss too. But a bankrupt inventor couldn’t get a perforating machine built. The Lumiere Brothers would also favour round perforations over the square ones of the Edison/Eastman format.

And we see he chose to move away from the square picture format of his earlier cameras, which had probably been influenced by the shape of lantern slides, and instead settled on a rectangular ratio. When I measured this, I discovered it was almost precisely the one that would later be adopted as the film industry standard for many long years – the 1.33:1 ratio, which would later be known as Academy Ratio.

“So, wouldn’t it be great if we could watch that film?” I hear you say.

Yep, it sure would. I mean, you can just hop on YouTube and see the earliest experiments from all the other pioneers like Donisthorpe & Crofts, Le Prince, Demeny, the Skladanowsky Brothers or Edison & Dickson. So where’s that Friese-Greene film? Well, still tucked away in the French archive of the CNC (Centre National de la Cinématographie) in Bois d’Arcy outside Paris. As I mentioned last time, they did preserve it and also made a copy on 35mm that could be projected. It had its world premiere in a collection of restored very early films from the Will Day Collection (see Part 2) at the Pordenone Festival of Silent Film on 16th October 1997.

I got my chance to see it (and some other Friese-Greene experiments) seven months later at the Duke of York’s in Brighton as part of a Colloquium on “Will Day and Early British Cinema” which I had been invited to participate in, having inadvertently become the world “expert” on Friese-Greene (a status that I have now expanded and built upon to no discernible financial advantage). It was a really glorious thing to see those early images up there on the cinema screen, where Friese-Greene imagined them but probably never saw them.

And then it went on a tour all over the world and everybody was finally able to see it.

Just kidding. It went back to the CNC and was put back in storage for a very, very, VERY long time with no video copy made available. Just now I came across a blog from a film programmer who says it was screened once more at an event in Helsinki in 2009. As far as I can tell those are all the outings it’s had in 21 long years.

The people I knew at the CNC are long gone. I have tried to make contact via the Cinématheque Française, but have got no response. So I began to think about those photos I took of the negatives back in 1996. They were done in a rush in totally non-ideal conditions – hand-held over a lightbox – but I wondered if there was enough information there to get something out of them. So I had my negatives (of the negatives) scanned at high resolution and asked a professional photographer to help put them into something like the right relative size and proportions, as they originally were. And then I made them move…

You see? I said I had something special for you.

Now, you must remember that each of the original Friese-Greene negatives only made up one ninth of the size of my 35mm frame. And the original Friese-Greene negative was about three times the size of a 35mm stills frame. Technically speaking, that means the original had over 25 times the resolution of what you see here (plus not all of my shots were dead-on in focus). Even allowing for the fact that film emulsion back then was a lot coarser, they would still have looked 10 times better than this.

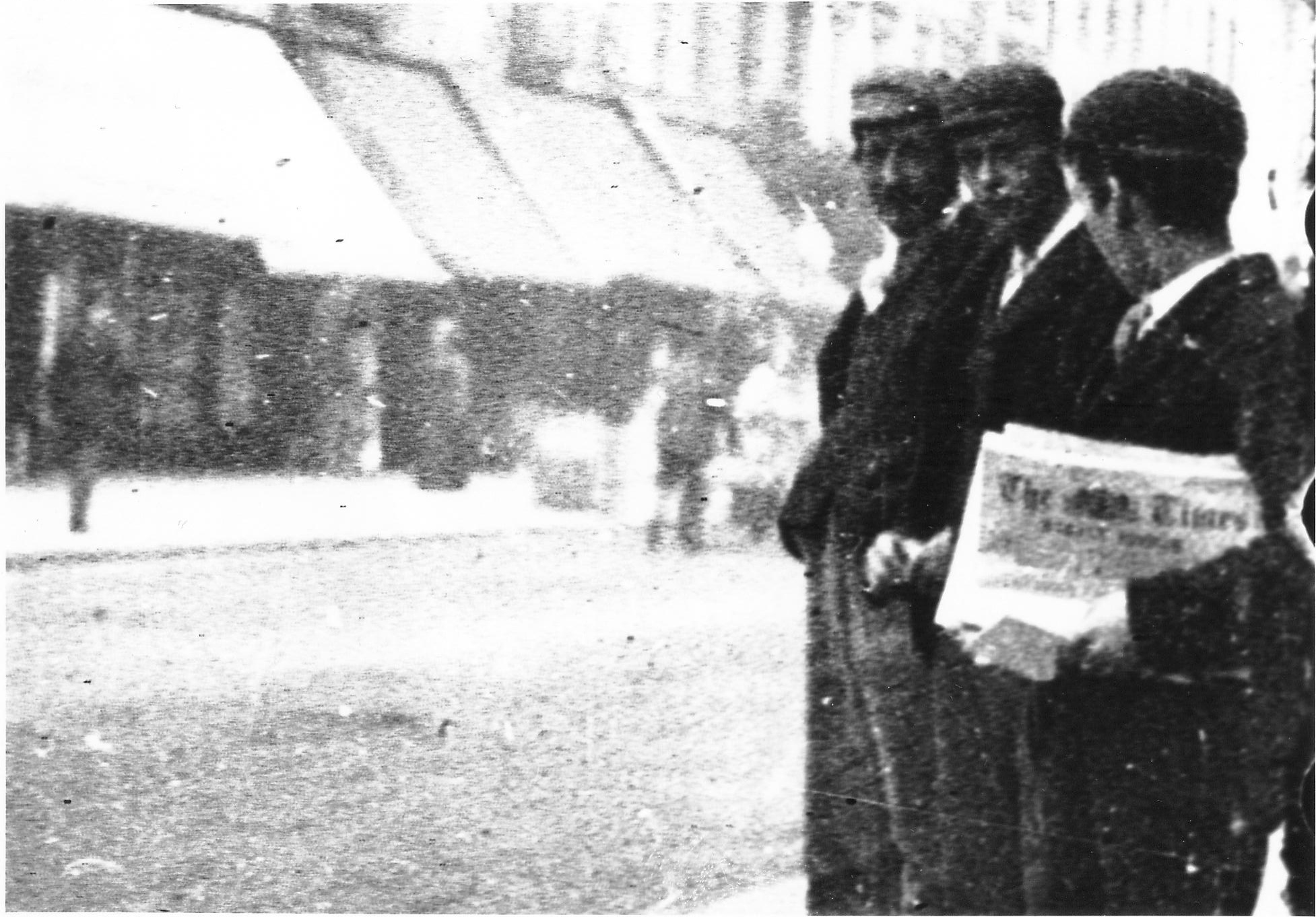

The proof of this is an enlargement of part of one frame, which I must have somehow acquired from the CNC some 20 years ago:

The name of the newspaper the boy is selling is clearly legible. I can’t help wondering if, with modern scanning techniques, we might be able to see something of the headline, which would help a lot with dating.

Speaking of dating, I did promise to date this film in Part 3 so here goes:

It was shot around the middle of 1891. I can’t be more specific than that (until we can read that newspaper). Why that date? Well…

The view you’re looking at is from close to the front of 39 King’s Road, Chelsea, which Helena Friese-Greene had used her own resources to rent, providing a home for her daughter and sisters, a photographic studio to make money and a basement workshop to keep her husband from going crazy with boredom. We know that at the start of 1891 they had already abandoned their rather lovely Maida Vale home and were holed up in temporary digs in Paddington. They appear to have moved to this address later in the year. It makes sense he would have shot the film when he lived there, not before.

That said, as we’ve already seen, William Friese-Greene now had absolutely no way to build any new cameras or other inventions. So whatever this was shot with had already been built in 1890. He may of course have adapted it in some way, and this was a test of the new arrangement. He would not be discharged from his bankruptcy until 1894 and, until then, all he could use was his ingenuity. Since he had been on a roll with a non-stop series of moving picture camera experiments over the previous two years, it makes sense this was part of that – before his mind moved on to other inventions.

And the time of year? Well, this is Britain. People don’t normally go about dressed like that in autumn or winter.

But it occurs to me that by some terrible oversight, I STILL have failed to explain why this constitutes a Eureka Moment for William Friese-Greene. However, I fear I would once again be trying your patience to go an any longer right now…

If you’d like to stay up to date with information on Mr. F-G and early cinema, pop your email below:

And if there’s something you’d like to ask me or tell me, go ahead:

Hi Peter, if you have difficulty with newspaper historians in tightly dating the masthead of The Times (Weekly Edition), maybe check copies – pre-arranged British Library visit – of an 1889, 1890, 1891, and 1892 issue to see whether this helps determine the timeframe for that masthead? (They might be online, but only accessible by institutions that subscribe.) I’m assuming the weekly edition for that period has been kept by the BL. Or maybe you’re past that stage already! Looking forward to the next installment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the thought, Mr Muybridge. A trip to the British Library is on the cards to check a number of things so I shall add that to the list, although I may be able to access archive copies another way. There are also other reasons for the dating, as we shall see in the next instalment…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I should also add that I was already able to find examples of the masthead of The Times Weekly Edition from 1885 and 1898. They were identical to each other and looked like the one in this picture. Nonetheless, there’s a chance that some kind of variation in layout or styling in between those dates might offer a small clue of some kind.

LikeLike

The mastheads for 1885 and 1897 that I’ve seen look the same as each other, but different to the one in the film. In that one the centre logo is shorter, and the lower text (WEEKLY EDITION) is spaced differently.

LikeLike