Every story of an inventor needs its “Eureka!” Moment where the forces of the universe combine with sleepless slog to generate the breakthrough that he/she has been striving for. In the 1951 film about William Friese-Greene, The Magic Box, this is depicted in a famous sequence where the sweating, pop-eyed, near-hysterical inventor drags a policeman off the street in the middle of the night to witness the first projection of moving pictures, with the PC believing he is about to hear the confession of a madman at the scene of a terrible crime.

Robert Donat is absolutely wonderful in it, perfectly capturing the agony and ecstasy of invention, and Laurence Olivier does a lovely cameo turn as the wary constable. It is in fact a marvellous movie scene, a bit of a classic even.

Pity then, that it’s a load of rubbish.

As any pedantic film historian will tell you; that device he’s using was not created until after the time the scene theoretically takes place (in 1889) and was originally patented by a collaborator of Friese-Greene as a stereoscopic (3D) camera (although Friese-Greene later patented something VERY similar and said it could be used as a projector, but that’s another story). Also, how did he turn a negative film into a positive film to project? And Friese-Greene himself never even told a story about doing his first projection to a policeman. It all seems like Chinese Whispers across 60 years.

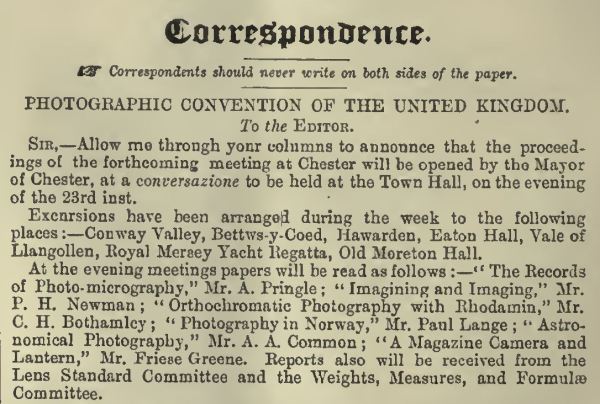

Early film historians would have it that his Eureka Moment should have been a demonstration before the Photographic Convention in Chester in the June of 1890 where he was to exhibit his motion picture camera, along with strips of film shot with it, and project said film with a new kind of “lantern”. However, these same historians would go on to assert that contemporary reports reveal it to have been a humiliating failure and that after that date there is no record of him projecting motion pictures. So, therefore he never had that Eureka Moment.

Early film historians would have it that his Eureka Moment should have been a demonstration before the Photographic Convention in Chester in the June of 1890 where he was to exhibit his motion picture camera, along with strips of film shot with it, and project said film with a new kind of “lantern”. However, these same historians would go on to assert that contemporary reports reveal it to have been a humiliating failure and that after that date there is no record of him projecting motion pictures. So, therefore he never had that Eureka Moment.

Was his Chester Convention turn really such a failure? Did he not project anything? That is the subject for another blog post. But one thing is clear: if it had been a resounding success, then the world would have heard about it. It would also have been quite extraordinary that one man beat Edison’s team, with all their massive resources by three whole years, in terms of successfully shooting on celluloid film, and beat the Lumières, with their considerable resources, by five years in terms of projection.

So is that it? No Eureka Moment?

Let’s rewind. There is no question that by 1890, Friese-Greene had been grappling with the issue of capturing motion in a camera and then synthesising it through projection for quite some years. This began with magic lantern experiments with John Rudge back in Bath from 1880 and carried on in a variety of forms. In spring 1889 Friese-Greene is to be found at the Crystal Palace Photographic Exhibition demonstrating a large, clockwork-driven, twin-lens projector which can rapidly display a long series of photographic slides to create a semblance of motion. It’s unwieldy in size and not entirely successful.

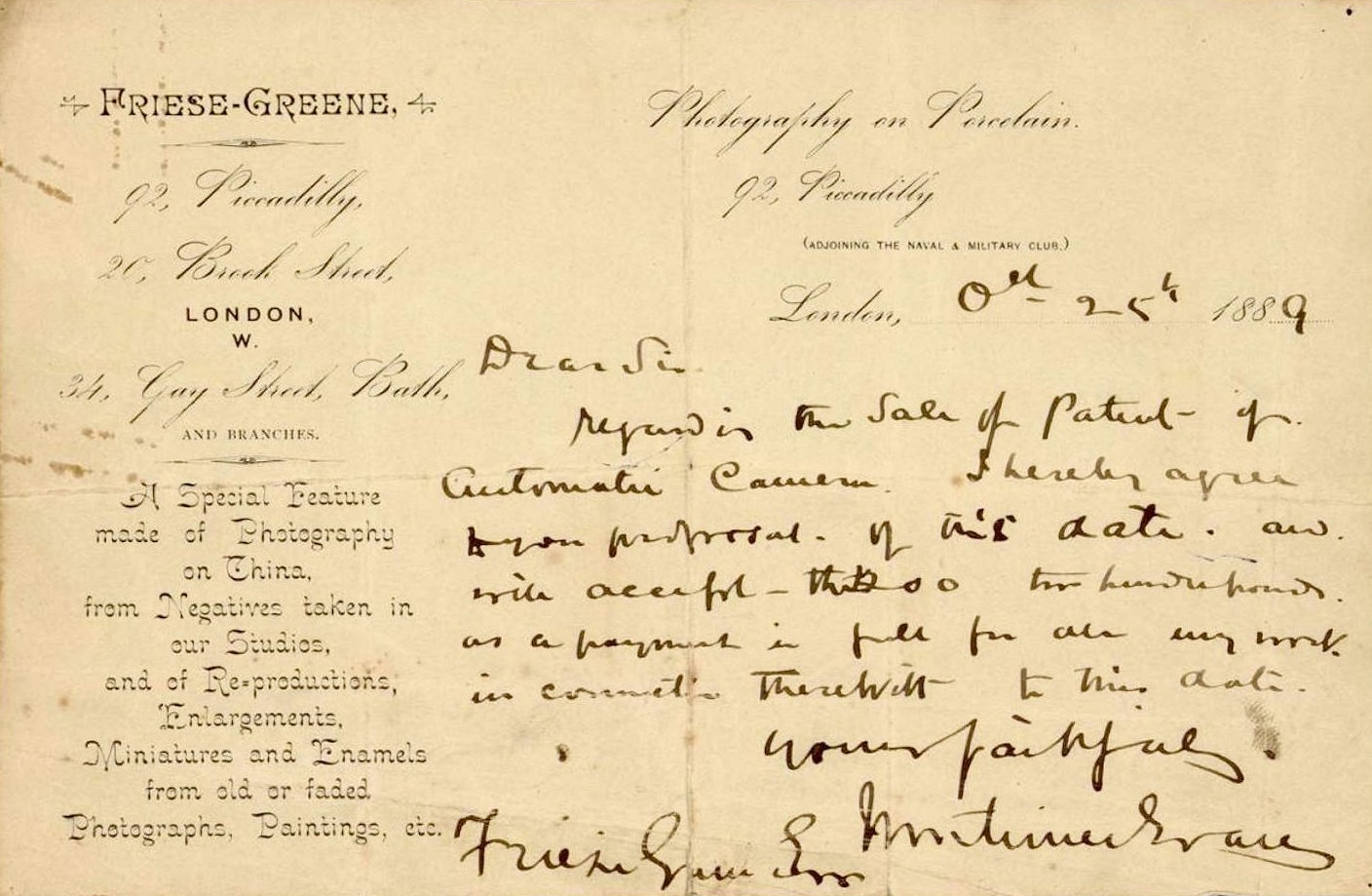

But by June he has moved on decisively and taken out the provisional patent for a single-lens camera that can record motion on an intermittently-moving strip of film. The working camera is ready on September 26th. He’s confident enough in its worth to buy out Mortimer Evans, the engineer who worked with him on it, for the princely sum of £200 – that’s £24,000 in today’s money – just one month later.

Of course, at this moment, the only rolls of film are paper negative, but word has already reached British shores of the Eastman celluloid films that are coming. Furthermore, Friese Greene has been visiting the impressive Paris Exposition over the summer and, apart from taking in the newly-built Eiffel Tower, was no doubt also getting eyeful of the “Balagny” celluloid film shown there, now being produced in rolls of up to 4 metres by 40cm for photographers – much of it from the Lumière factory. So he knows it’s just a question of time before longer, narrower, more flexible rolls start coming in from the United States – which will be exactly what he needs for his camera.

They hit the British market in February 1890 and within days he is showing off his new invention to the world. Within weeks he has not only shot long strips of celluloid with it, he’s already handing these around at photographic societies. But how is he going to create a positive from the negative – which is what one needs, to do a screening – and how is that positive film going to be projected?

The Chester Convention that summer was where one might have hoped to find the answers, but the official records don’t provide them. (Sorry, you’ll have to wait for that other blog post.)

Although he moved on to work with another engineer, Frederick Varley, and they showed off a new camera that autumn – a stereoscopic one – along with film shot with it, still there was no word of projection and then….

Disaster

On the face of it, Friese-Greene had been doing very well. His chain of photographic studios had been expanding, he’d photographed royalty, he was all over the photographic journals and the international press, his Opal Card Company had been launched with much fanfare and funds. But he had spent all of his profits and considerably more on inventing and, in a very Dickensian way, his debtors had been circling and all descended at once. His financial carcass was picked clean and suddenly all press reports of him stopped.

On February 7th 1891 – just 10 months since his first camera was featured in Scientific American, 3 months since opening his latest photographic studio and 10 weeks since he showed off his latest motion picture camera in public – he has all of his worldly belongings sold at auction to pay off debts. EVERYTHING; from the finest porcelain to his copies of The Photographic News. Even the two custom lanterns (projectors) he bought from his early mentor John Rudge to create movement through photographic slides, plus that big, expensive projector he had shown at Crystal Palace less than two years before. It’s doubtful these bizarre latter items got much interest from a crowd looking to snap up some quality carpets and furniture at bargain basement prices.

On February 7th 1891 – just 10 months since his first camera was featured in Scientific American, 3 months since opening his latest photographic studio and 10 weeks since he showed off his latest motion picture camera in public – he has all of his worldly belongings sold at auction to pay off debts. EVERYTHING; from the finest porcelain to his copies of The Photographic News. Even the two custom lanterns (projectors) he bought from his early mentor John Rudge to create movement through photographic slides, plus that big, expensive projector he had shown at Crystal Palace less than two years before. It’s doubtful these bizarre latter items got much interest from a crowd looking to snap up some quality carpets and furniture at bargain basement prices.

Days later he is up in court, facing the lawyers of the Electricity Company alongside another former business partner, Esme Collings (Friese-Greene championed the use of electric light for portrait photography). In June, bankruptcy proceedings begin against the Opal Card Company, of which he is the Managing Director. His personal bankruptcy proceedings follow soon after. Having had to divest himself of most of his studios, his Christmas present is the winding-up of the Opal Card Company and the final totting up of his personal affairs, which is published both nationally and, for double humiliation, in his home town of Bristol: “The unsecured debts are returned at £2,153, with available assets nil.” He was a quarter of a million down, in today’s terms.

The Friese-Greene household has to downsize rapidly and dramatically. They move into a house on the Kings Road, which becomes a home upstairs and a photographic studio downstairs, with a basement which could be used for something. Only his more financially astute wife Helena is allowed to have her name on the business. She employs him as her manager on a salary of £2 per week. That’s about on a par with a Deliveroo driver, which is to say; barely making the minimum wage. William Friese-Greene is broke and broken.

Or is he?

The story continues HERE

If you want to stay up-to-date with Mr F-G just pop your email address here:

And if there’s something you’d like to ask me or tell me, go ahead:

Hi FrieseGreeneGuy, Very pleased that you’ve started this blog! I well remember introducing you to Brian Coe all those years ago, and the somewhat awkward conversation that followed. And of course, we will always have Paris…..

Since then, I’ve been involved with reproducing three “Friese Greene” cameras. Tests were interesting – I shot a couple myself on the stereo camera. That was – a struggle. And when our project engineer handed over the replica of the (missing) 1889-ish camera, it was with a “don’t try to run it faster than 5fps, or you’ll strip the gears” – which might explain a lot. I like your engaging writing style, and look forward to reading more – fascinated to know what you’ve discovered about F-G projecting in 1890. I hope you’ll be detailing the background and work of Evans (mechanical, electrical, and optical) and Varley (optical, electrical) some time. Finally; That clip from The Magic Box is one of my favourite moments in all of cinema. A classic, certainly.

Stephen.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for the encouragement, mysterious Muybridge person (who turns out to be called Stephen). Yes, I think Trump being shown around the Whitehouse by Obama may have been a more chilled out affair than me and Mr Coe. I still used his books for research, though (Brian Coe that is, not Donald Trump).

I’m very much looking forward to getting together sometime soon to talk about those tests and hope somehow to see the cameras themselves and have a chance to examine and fiddle with them, in your company.

Yes, I am planning a series of posts on Friese-Greene’s key early collaborators: Rudge, Evans and Varley. My thoughts about the last of these three pretty much turn former thinking on its head.

And the Chester Convention will have its moment in the spotlight. But first I have to finish looking for That Eureka Moment…

LikeLiked by 1 person